Bust of Hippocrates, Engraving 1638, Paulus Pontius (after Rubens)

The February 2025 Art In Medicine topic is about Hippocrates.

Lucinda Bennett, the Medical Librarian at Ascension St Agnes Hospital in Baltimore, MD, publishes a regular series on Art in Medicine and The Health Humanities.

It's only 1-2 pages with gorgeous images, so it won't take you long to read

... and just might enrich your life.

Hippocrates

In the history of the medical arts, there is possibly no more familiar name than Hippocrates. Considered the father

of medicine, Hippocrates’ name is invoked by all graduating physicians, his texts read in a great many classes and

his image shared in various media across time and place. However, as is usually the case, history is often clouded

by myth and this storied doctor is no different. So who was he

really, do we actually know what he looked like, and are his

writings truly written by a single author?

“Hippocrates (born c. 460 bce, island of Cos, Greece—died c. 375

bce, Larissa, Thessaly) was an ancient Greek physician who lived

during Greece’s Classical period … It is difficult to isolate the facts

of Hippocrates’ life from the later tales told about him or to assess

his medicine accurately in the face of centuries of reverence for

him as the ideal physician. About 60 medical writings have

survived that bear his name, most of which were not written by

him. He has been revered for his ethical standards in medical

practice, mainly for the Hippocratic Oath, which, it is suspected,

he did not write. It is known that while Hippocrates was alive, he

was admired as a physician and teacher. His younger

contemporary Plato referred to him twice. In the Protagoras Plato

called Hippocrates “the Asclepiad of Cos” who taught students for

fees, and he implied that Hippocrates was as well known as a

physician as Polyclitus and Phidias were as sculptors.”

(Britannica)

At the time Hippocrates was living and practicing, the perspective

of where medicine lay within ancient Greek life was much

different than how we view that field today. In fact, it was

considered an art rather than a science, which was not yet fully formed as a discipline. As such, the philosophy which Hippocrates was taught and would later teach via medicine, approached treatment of the sick in a manner that is alien to many today. “The term art is used very often, especially in Plato, however, the ancients separated art from other (after intellectual disciplines. Even when they perceive art in this more limited way, they

always tend to include medicine among the arts, such as shoemaking, woodworking, agriculture, rhetoric and

poetry, for the reason that medicine generates health. By creating health, medicine seems both, poetic and utilitarian

art because physicians use a variety of tools and methods in order to achieve health for their society. Since medicine

is the most important of the arts, those who are going to follow it are required to have many spiritual and moral

qualifications if they wish to serve it properly.” (Philosophy & Hippocratic Ethic)

Encyclopedia Britannica states the documents attributed to Hippocrates contain various theories, tones of writing,

and evidence that these works were the cumulative experiences of several individual authors. As with many ancient

texts, they were added to, translated and altered over the centuries. By all accounts Hippocrates was a real man, but

wrote only a fraction of works bearing his name. Still, his impact was felt after his death in the manner in which later scholars and artists would interact with his body of work and even his appearance. “Hippocrates’ reputation,

and myths about his life and his family, began to grow in the Hellenistic period, about a century after his death.

Hippocrates Refuses the Gifts of Artaxerxes, Painting

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trioson, 1792

During this period, the Museum of Alexandria in

Egypt collected for its library literary material from

preceding periods in celebration of the past

greatness of Greece. So far as it can be inferred, the

medical works that remained from the Classical

period (among the earliest prose writings in Greek)

were assembled as a group and called the works of

Hippocrates (Corpus Hippocraticum). Linguists and

physicians subsequently wrote commentaries on

them, and, as a result, all the virtues of the Classical

medical works were eventually attributed to

Hippocrates and his personality constructed from

them.” (Britannica) In later centuries these texts

were then expanded upon by Muslim physicians,

further carried the teaching of Hippocrates into a new era, codifying his theories on illness. “By translating masterpieces of Greek learning into Arabic, which would be eventually rendered into Latin, scholar-physicians such as Haly Abbas, Rhazes, Avicenna, and Albucasis performed the extraordinary miracle of reintroducing Greek authors into Western Europe, including Hippocrates and Galen.” (The

Art of Science & Healing) By the modern era, fictions blurred with fact as to what this famous physician did or did

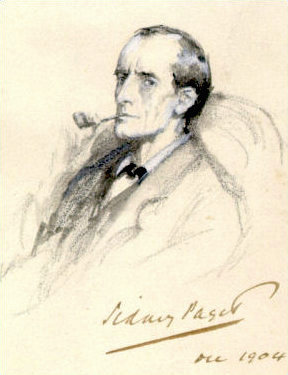

not do. In fact, even his appearance is not honestly known. The elderly man with short hair and a full beard is an

archetype typical of Classical Greece, not a means of true portraiture. How we imagine Hippocrates could be just as

fictional as some of the stories attached to him, such as the instance with the King of Persia, as depicted here. “The

painting is based on a historical and legendary episode that occurred during the reign of Artaxerxes I, when Persia

was ravaged by a devastating plague. In a desperate attempt to save his kingdom, the Persian king sent ambassadors

to Greece to request the help of Hippocrates, the most renowned healer of his time. Artaxerxes offered lavish gifts

and large sums of money to persuade Hippocrates to come to Persia and eradicate the plague. However,

Hippocrates, staying true to his homeland and his ethical principles, rejected the king’s offer. Despite the wealth and

rewards he was promised, Hippocrates chose to remain in Greece, refusing to aid the enemies of his country, even

though it meant forgoing great riches. Soon after, the same plague spread to Greece, affecting the land Hippocrates

had chosen to protect.” (Art Insider)

References:

Hippocrates - Encyclopedia Britannica

The Art Insider

Philosophy and Hippocratic Ethic in Ancient Greek Society: Evolution of Hospital - Sanctuaries

The Art of Science and Healing: From Antiquity to the Renaissance

Reprinted with the generous permission of Ms. Bennett.

![]() This image is released under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License

This image is released under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License